4. Burlesque v. Irony

Burlesque v. Irony - Notes

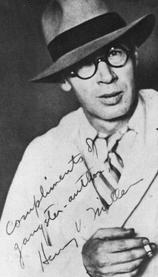

1Epigraph: Henry Miller, Black Spring (Paris: The Obelisk Press, 1938; New York: Grove Press, 1963), 226, 227.

2 Kingsley Widmer, Henry Miller (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1963), 157. Kingsley Widmer proposes to "put a responsive but sharp knife to Miller's conglomerate writings: to cut away the fat and to probe some of the major themes, meanings and qualities which give Miller significance for our literature and sensibility" (7). Unlike Frank Kermode, however, who in "Henry Miller and John Betjeman" from Puzzles and Epiphanies knows precisely the New Critical "mesure" of his critical knife, Widmer, to the extent to that he listens to Miller's persuasive rhetoric of excess, is uncertain as to the aesthetic principles he should employ upon Miller's corpus. As a result, after a page and a half listing of the American writers in debt to Miller--William Saroyan, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsburg, Gregory Corso, William Borroughs, Nelson Algren, Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, Norman Mailer, J. P. Donleavy, in short a huge slice of the American avant-garde of the post-war years, embracing nostalgic portraiture, urban, ethnic and psychoanalytic exploration, and the Beats as they modulated into New Journalism--after all this; after concluding that the "discordant lyric, the aslant picaresque, the personal reverie, the satiric apocalypse, and, especially, grotesque poetic comedy seem the most likely and responsive forms for the present," Widmer quietly "suggests" that "Miller is a minor writer," who "may--in his best work--have a major relevance" (156-157).

3 Kingsley Widmer, Henry Miller, 27, 155-156.

4 Henry Goddard, The Kallikak Family (New York, 1911). See Richard Hofstadter, Social Darwinism in American Thought (New York: Beacon Press, 1955), 164.

5 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 35, 88, 2.

6 Henry Miller, Black Spring, 226-227.

7 Henry Miller, Black Spring, 230.

8 Job, quoted in "Epilogue" to Moby-Dick, or The White Whale by Herman Melville (1851). Ishmael, like Miller, is a drifter, a personae with little depth or weight, who survives by floating upon surfaces.

9 Walter Benjamin, "The Storyteller," Orient und Okzident (1936); quoted from Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zorn (Schocken Books, 1969), 102-103.

10 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 9.

11 Henry Miller, Introduction to Bastard Death by Michael Fraenkel (Paris: Carrefour, 1936), 39. Reprinted as first letter in Henry Miller and Michael Fraenkel, Hamlet (Santurce, Puerto Rico: Carrefour, 1939), Vol I.

12 Kingsley Widmer, Henry Miller, 27, 155-156.

13 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 45.

14 Widmer writes as if Miller's burlesque narrative must "emphasize, at any cost, the subjectivity of the narrating author," merely because it is "auto-biographical" (Kingsley Widmer, Henry Miller, 20).

15 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 1.

16 Henry Miller, Black Spring, 235; "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye (1939; New York: New Directions Paperbook, 1961), 128. The Cosmological Eye contains a number of essays originally published in Max and the White Phagocytes (Paris: The Obelisk Press-Seurat Editions, 1938). The 1961 paperbook reprint appends one essay, "The Cosmological Eye," not included in the 1939 hardbound edition.

17 M. M. Bakhtin, "Forms of Time and Chronotrope in the Novel," in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin, trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, ed. Michael Holquist (1981; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 159, 163.

18 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn (Paris: The Obelisk Press-Seurat Editions, 1939; New York: Grove Press, 1961), 48.

19 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 223.

20 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 37.

21 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 36.

22 The phrase "anatomists of the soul" links this passage to Miller's critique of the 'urban planning' of Ulysses. Miller uses the same phrase in "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye, 130:

When one day the final interpretation of Ulysses is given us by the "anatomists of the soul" we shall have the most astounding revelations as to the significance of his work. Then indeed we shall know the full meaning of this "record of diarrhoea". Perhaps then we shall see that not Homer but defeat forms the real ground-plan, the invisible pattern of the work.

Miller's notion of "defeat" encompasses a tremendous will to power. Ulysses, the dead city of abstractions, defeats the living city street.

23 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 222.

24 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 63.

25 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 68.

26 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 69, 70.

27 D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (London: Thomas Seltzer, 1923; New York: Viking Press-Viking Compass Book, 1964), 146.

28 Henry Miller, "Into the Future" ["Fragment from The World of Lawrence"--author's note], in Henry Miller, The Wisdom of the Heart (1941; New York: New Directions, 1960), 165.

29 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 63.

30 Henry Miller, Introduction to Bastard Death by Michael Fraenkel, 40: "The life of this form depends, not upon a stable equilibrium, but on a fluid imbalance."

31 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 70.

32 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 71. Suggesting more "popular" sources for Joyce's myth-making, the "Joycean" limerick mocks Stuart Gilbert's hopelessly erudite, circuitous explanation of the "Dubliners-Vikings-Achaeans" connection in Ulysses:

Speaking of this expedition, Depping (Histoire des Expéditions Maritimes des Normans) records that the Scandinavians sailed up the Guadalquivir and, having defeated the Moors who opposed their attack on Seville, pillaged the city and retired to their ships "bringing with them much booty and a crowd of prisoners, who perhaps never again beheld the beautiful sky of Andalusia." [....] There are many references to Moors in Ulysses, to the Moor Othello, to "morrice" (Moorish) dances, "imps of the fancy of the Moors", "the nine men's morrice with caps of indices", and to Mrs. Bloom's "Moorish" eyes which, after her marriage with Leopold Bloom, never again beheld the beautiful sky of Andalusia.

(Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce's 'Ulysses', 67-68)

33 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West (New York: Random House-The Modern Library, 1962), 266. "An abridged edition by Helmut Werner. English abridged edition prepared by Arthur Helps from the translation of Charles Francis Watkins." Originally published in two volumes as Der Untergang des Abendlandes, Gestalt und Wirklichkeit and Der Untergang des Abendlandes, Welthistorische Perspektiven (Munich: C. H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1918 and 1922). First American publication: The Decline of the West, Volume I: Form and Actuality and The Decline of the West, Volume II: Perspectives of World-History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926 and 1928).

34 Ralph Waldo Emerson, "VIII. Prospects," in Nature (1836); reprinted in Emerson, Essays and Lectures, ed. Joel Porte (New York: Library of America, 1983), 48-49:

Build therefore your own world. As fast as you conform your life to the pure idea in your mind, that will unfold its great proportions. A correspondent revolution in things will attend the influx of the spirit. So fast will disagreeable appearances, swine, spiders, snakes, pests, mad-houses, prisons, enemies, vanish; they are temporary and shall be seen no more. The sordor and filths of nature, the sun shall dry up and the wind exhale.

Tropic of Cancer mocks the cleanliness of Emerson's "Prospects". Miller replies, all out of proportion, all out of his mind:

Today I awoke from a sound sleep with curses of joy on my lips, with gibberish on my tongue, repeating to myself like a litany--"Fay ce que evouldras! . . . fey ce que vouldras!" Do anything, but let it produce joy. Do anything, but let it yield ecstasy. So much crowds into my head when I say this to myself: images, gay ones, terrible ones, maddening ones, the wolf and the goat, the spider, the crab, syphilis with her wings outstretched and the door of the womb always on the latch, always open, ready like the tomb. Lust, crime, holiness: the lives of my adored ones, the failures of my adored ones, the words they left behind them, the words they left unfinished; the good they dragged after them and the evil, the sorrow, the discord, the rancor, the strife they created. But above all, the ecstasy!

(Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 227-228.)

35 Ralph Waldo Emerson, "VIII. Prospects," in Nature (1836); reprinted in Emerson, Essays and Lectures, 48.

36 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 63-64.

37 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 64-65.

38 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 65.

39 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 65.

40 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 65-67. This parity is the ground of urban friendship, announced on the first page of Tropic of Cancer:

Last night Boris discovered that he was lousy. I had to shave his armpits and even then the itching did not stop. How can one get lousy in a beautiful place like this? But no matter. We might never have known each other so intimately, Boris and I, had it not been for the lice.

41 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 136.

42 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 212.

43 I. A. Richards' "modernization" of Coleridge largely consists of stripping the "magic" from the Romantic's "synthetic and magical power." See Principles of Literary Criticism (1925; New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich-A Harvest/HBJ Book, n.d.), 189, 242, for Richards' selective quotation from Coleridge's Biographia Literaria, II, 12, 14, and his "setting aside" of the inevitable "Transcendentalism" remaining in the passages cited.

44 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 235. Crucial to the rise of New Critical modernism, I. A. Richards' understanding of irony represents Frank Kermode's "mesure" in the first flush of its universal aspiration. Beneath his talk of "the tradition" Richards knows he is the advocate of a critical revolution which will change the "universe" of literature, and, unlike Kermode thirty years later, Richards is untroubled by his advocacy. Quite simply, Richards is Miller's contemporary, partaking of the general fervor of a moment in our literary history when the very nature of literature seemed "up for grabs."

The "freedom" and "increased competence" I. A. Richards promises his readers are no more real than Miller's "I'm free--that's the main thing. . ." As competing aesthetic ideologies, New Critical modernism and Miller's alternative modernism both claim to be paths to freedom: both are equally implicated in wishful "philosophies of life." It is due to the hegemony of New Critical modernism that we tend to see such contrasting "philosophies of life" as an opposition between New Critical art and intellect, and Miller's "philosophy of life." That is, Miller's narrative technique appears subordinated to a "philosophy of life," whereas the "philosophy of life" promulgated by New Critical modernism tends toward invisibility.

45 Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Essay on the Principles of Genial Criticism. Quoted significantly in Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce's 'Ulysses', 24n. On Coleridge's own secularizing tendencies see M. H. Abrams, Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature (1971; New York: W.W. Norton & Company-Norton Library, 1973).

46 The fully ironized, ideal New Critical reader cannot determine what is ironic and what is not.

47 Jonathan Swift, "The Preface of the Author," in The Battle of the Books (1704).

48 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 251. Richards refers in a footnote to the discussion of "equilibrium" in The Foundations of Aesthetics by I. A. Richards and C. K. Ogden (London: Allen & Unwin, 1922).

49 Much effort has gone into converting Swift's satiric corpus into a reflection of the New Critical understanding of ironic ambivalence, attempting to "tragically balance" Swift's distaste for Ireland and his resentment of the English with his commitment to the Irish cause and admiration for English letters. While it is possible to psychoanalyze Swift and his work and so make coherent sense of their "tensions," it is equally possible to state flatly that the man was simply outraged that anyone, including himself and the Irish, should be forced to "live the life of the Irish" within the British empire. This is a straightforward social/political position--no ambiguity, no tensions, no ironic balance, no need for psychoanalytic explanation.

50 In this sense, irony and satire remain measurable by that which they set out to oppose.

51 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 248.

52 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 1.

53 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 184, 247, 248. Richards' phrasing, "balanced poise, stable through its power of inclusion, not through its force of exclusions" presents an effective description of the workings of hegemony, appropriating everything of value to itself, excepting only "unstable" works and individuals.

54 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 248, 234. Sir Cyril Burt was instrumental in orchestrating the English system of testing and school assignment. His work with twins sought to demonstrate that intelligence was hereditary. Subsequently it was discovered that he forged his data. See Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasurement of Man (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983).

55 I. A. Richards' claims were so extensive that even T. S. Eliot balked:

We cannot of course refute the statement 'poetry is capable of saving us' without knowing which one of the multiple definitions of salvation Mr. Richards has in mind. [Continued in a footnote] There is of course a locution in which we say of someone 'he is not one of us'; it is possible that the 'us' of Mr. Richards's statement represents an equally limited and select number.

(T. S. Eliot, "The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism," in Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot, ed. Frank Kermode [New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich and Farrar, Straus and Giroux--A Harvest/Noonday Book, 1975], 88. Lectures delivered at Harvard University 1932-33; first published in 1933.)

Eliot identifies, albeit to demure, the dynamic whereby Richards defines and then seeks to universalize an 'us' that embraces Eliot. But Eliot, no less than Richards, was a polemicist. It is only that in this instance Richards' bravura is more revealing than Eliot's false modesty.

56 See Friedrich Nietzsche, "On Truth and Falsity in their Ultramoral Sense," in The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, ed. Oscar Levy (London: Unwin & Allen, 1911), II, 117; and Jacques Derrida, "White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy," in Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982). Originally published in French in Poétique 5 (1971). A previous translation by F. C. T. Moore appeared in New Literary History 6, no. 1 (1974).

57 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 183.

58 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 332.

59 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism, 235.

60 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 7, 8.

61 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 8.

62 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 8-9. Miller casts Fraenkel in the role of paradigmatic Modernist:

There are people who cannot resist the desire to get into a cage with wild beasts and be mangled. They go in even without revolver or whip. Fear makes them fearless. . . . For the Jew the world is a cage filled with wild beasts. The door is locked and he is there without whip or revolver. His courage is so great that he does not even smell the dung in the corner. The spectators applaud but he does not hear. The drama, he thinks, is going on inside the cage. The cage, he thinks, is the world. Standing there alone and helpless, the door locked, he finds that the lions do not understand his language. Not one lion has ever heard of Spinoza. Spinoza? Why they can't even get their teeth into him. "Give us meat!" they roar, while he stands there petrified, his ideas frozen, his Weltanschauung a trapeze out of reach. A single blow of the lion's paw and his cosmogony is smashed. The lions are disappointed too.

Tropic of Cancer describes the secularized Jewish intellectual as Modernist, but Miller uses the same language to describe Joyce in "The Universe of Death":

Through the mystery-throngs he weaves his way, a hero lost in a crowd, a poet rejected and despised, a prophet wailing and cursing, covering his body with dung, examining his own excrement, parading his obscenity, lost, lost, a crumbling brain, a dissecting instrument endeavoring to reconstruct the soul. Through his chaos and obscenity, his obsessions and complexes, his perpetual, frantic search for God, Joyce reveals the desperate plight of the modern man who, lashing about in his steel and concrete cage, admits finally that there is no way out.

(Henry Miller, "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye, 110)

63 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 9.

64 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 10.

65 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 25.

66 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 10.

67 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 10.

68 Henry Miller, Introduction to Bastard Death by Michael Fraenkel, 39.

69 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 240-241. The passage continues until it reaches the cosmos "shattered to bits" of Miller's letter in Hamlet:

The earth is parched and cracked. Men and women come together like broods of vultures over a stinking carcass, to mate and fly apart again. Vultures who drop from the clouds like heavy stones. Talons and beak, that's what we are! A huge intestinal apparatus with a nose for dead meat. Forward! Forward without pity, without compassion, without love, without forgiveness. Ask no quarter and give none! More battleships, more poison gas, more high explosives! More gonococci! More streptococci! More bombing machines! More and more of it--until the whole fucking works is blown to smithereens, and the earth with it!

70 Henry Miller, Introduction to Bastard Death by Michael Fraenkel (Paris: Carrefour, 1936), 39.

71 Henry Miller, Letter to Anaïs Nin (June 1933), in Henry Miller: Letters to Anaïs Nin, 95.

72 Henry Miller, "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye, 132-133.

73 Henry Miller, "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye, 132, 114.

74 Henry Miller to Anaïs Nin (October 1932), in Henry Miller: Letters to Anaïs Nin, 66.

75 James Joyce, Ulysses (Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922; New York: Random House-Modern Library, "New Edition, Corrected and Reset," 1961), 671, 672. Emphasis added.

76 James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (New York: The Viking Press, 1964; New York: Penguin Books, 1976). This passage is quoted significantly in Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce's 'Ulysses', 24. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was originally published by B. W. Huebusch in 1916. The Viking/Penguin text is corrected from the Dublin holograph.

77 Henry Miller, Introduction to Bastard Death by Michael Fraenkel, 39.

78 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 220, 220.

79 Henry Miller, Introduction to Bastard Death by Michael Fraenkel, 39, 40.