6. Diatribe v. Epiphany

Diatribe v. Epiphany - Notes

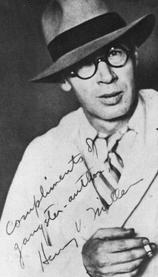

1 First Epigraph: Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer (Paris: The Obelisk Press, 1934; New York: Grove Press, 1961; New York: Ballantine Books, 1973), 232. Second Epigraph: Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn (Paris: The Obelisk Press-Seurat Editions, 1939; New York: Grove Press, 1961), 115, 116.

2 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 222-223. Frank Kermode's criticism, cited earlier is prefaced in this manner. (Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," in Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, ed. Edward B. Mitchell [New York: New York University Press, 1971].) Also, one of Miller's early idols of the previous generation, George Bernard Shaw, had a similar reaction: "This fellow can write: but he has totally failed to give any artistic value to his verbatim reports of bad language." (Jay Martin, Always Merry and Bright: The Life of Henry Miller (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Capra Press, 1978; New York: Penguin Books, 1980], 317.) Apparently, iconoclasm is not made of the same stuff from one generation to the next.

3 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 3.

4 Hart Crane, "To Brooklyn Bridge," in The Bridge (Paris: Black Sun Press, 1930), l. 19.

5 Edmund Wilson, "The Twilight of the Expatriates" The New Republic (March 9, 1938); reprinted in A Literary Chronicle: 1920-1950 (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company-Doubleday Anchor Books, n.d.), 211-214. A Literary Chronicle is a collection derived from Classics and Commercials (New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1950) and Shores of Light (New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1952), 211-214. In his title, although not in his review, Wilson recognizes the Nietzschean influence upon Tropic of Cancer's "modern vision."

6 When Miller does speak of the "whole system of American labor" in Tropic of Capricorn it is in terms of consequences produced by a system midway between accident and plan. He speaks of "statistical" sense and individual "pathology." The result is a social reality that cannot be captured by (natural/sexual) sublime figures of heights and depths--"it was worse than looking into a volcano, worse than a "worn-out cock":

It looked worse than that, really, because you couldn't even see anything resembling a cock any more. Maybe in the past this thing had life, did produce something, did at least give a moment's thrill. But looking at it from where I sat it looked rottener than the wormiest cheese. The wonder was that the stench of it didn't carry 'em off.... I'm using the past tense all the time, but of course it's the same now, maybe even a bit worse. At least now we're getting it full stink.

(Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 12-13.)

7 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 3.

8 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 1.

9 Herman Melville, "Chapter XXXVII: Sunset," in Moby-Dick, or The White Whale [1851], ed Charles Feidelson, Jr. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1964), 227.

10 Herman Melville, "Chapter XLI: Moby Dick," in Moby-Dick, 248-249.

11 It should not escape notice that the "modernity" of Moby-Dick centers upon Ahab rather than Ishmael. The Moby-Dick of the twenties and thirties was the tragedy of Ahab and the black-white symbolism of the whale. Ralph Ellison's adoption of Ishmael in The Invisible Man (1947; New York: Random House-Vintage Books, 1972) stands as a landmark in the interpretive history of Moby-Dick. Ellison's use of Ishmael rather than Ahab is of a piece with the recent critical interest in Ishmael as narrator, chronicler, and errant encyclopedist of whales. Ellison's black/white "symbolism," like Ishmael's, is eclectic, refusing to come to a point or even a stable ironic equilibrium. Their use of "symbolism" is similar to Miller's--burlesque and radically dispersive.

12 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 136.

13 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 231.

14 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 227.

15 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 115, 116. The flight Miller describes is more complex than my selective quotation reveals. It includes a complex negotiation with Emerson's "Circles" (Essays: First Series [1841]) which is played out over several pages. The flight must circle, because first Miller must die as a city before moving, silently, outward as a human being. The complexities are treated in my subsequent chapter, "The Last Book."

16 Within the "chapters," which vary from as short as ten to as long as sixty pages, the diatribes, when they do appear, are of equally various length. Extended anecdotal narrative does not go uninterrupted, however brief the eruption, and longer lulls, such as one covering three and a half "chapters" between pages 168 and 218, are compensated, in the noted instance with Miller's longest, fifteen page, rant.

17 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 257-258.

18 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 243.

19 D. H Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (London: Thomas Seltzer, 1923; New York: Viking Press-Viking Compass Book, 1964), 164.

20 D. H Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, 165.

21 D. H Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, 172. In a "post-mortem" world, Whitman's "post-mortem effects" are representative: "The individuality had leaked out of him. [....] If that is so, one must be a pipe open at both ends, so everything runs through." Miller's decisive break from Lawrence's "cult of the flesh" is inscribed in the seriousness with which Miller takes what Lawrence offers as a parody of Whitman on the "Open Road." Parody names the "subjectivity" Miller's "clown," his "Arabian zero." Those who insist upon Miller's unqualified adoration and (lowbrow) emulation of D. H. Lawrence have not read this passage attentively.

22 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 224.

23 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 230.

24 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 232.

25 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 231. Miller notes the "extra-temporal history" of Ulysses in "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye (1939; New York: New Directions Paperbook, 1961), 113. The Cosmological Eye contains a number of essays originally published in Max and the White Phagocytes (Paris: The Obelisk Press-Seurat Editions, 1938). The 1961 paperbook reprint appends one essay, "The Cosmological Eye," not included in the 1939 hardbound edition.

26 James Joyce, Ulysses (Paris: Shakespeare and Company, 1922; New York: Random House-Modern Library, "New Edition, Corrected and Reset," 1961), 59-61.

27 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 222.

28 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 9.

29 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 222.

30 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 222-223.

31 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 223.

32 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 184.

33 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 56.

34 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 225.

35 Henry Miller, "The Universe of Death, from 'The World of Lawrence,'" in The Cosmological Eye, 130-131.

36 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 88.

37 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 2.

38 In the branch of mathematics called topology, such a "container" is known as "Klein's bottle," which like the Mobius strip has only one surface, but unlike the Mobius strip has no edges. This is not to impute to Miller a knowledge of topology, but to say that in reaching for a description of time that cannot be imaged, Miller attributes to time characteristics that suggest counter-intuitive branches of mathematical speculation which also pass beyond the realm of visual representation. More plausibly, Miller's description of time is built on the analog of Augustine's (non)image of God, whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere.

39 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 88.

40 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 244-247.

41 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 17-18.

42 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 166-167. The passage continues:

[Mona] was leaning out of the window, just as she had leaned out of the window when I left her in New York, and there was that same, sad, inscrutable smile on her face, that last-minute look which is intended to convey so much, but which is only a mask that is twisted by a vacant smile. [....]

It is that sort of cruelty that is embedded in the streets; it is that which stares out from the walls and terrifies us when suddenly we respond to a nameless fear, when suddenly our souls are invaded by a sickening panic. It is that which gives the lampposts their ghoulish twists, which makes them beckon to us and lure us to their strangling grip; it is that which makes certain houses appear like the guardians of secret crimes and their blind windows like the empty sockets of eyes that have seen too much.

43 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 226.

44 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 226.

45 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 227.

46 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 227-228.

47 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 228.

48 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 245-246.

49 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 230-231.

50 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 150.

51 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 287