II. Narrative Detours: Strategy and Device

Narrative Detours: Strategy and Device - Notes

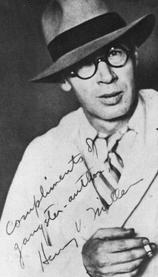

1 First Epigraph: Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce's 'Ulysses': A Study by Stuart Gilbert (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1930; New York: Random House-Vintage Books, 1955), 25. Second Epigraph: Henry Miller, "Burlesk," in Black Spring (Paris: The Obelisk Press, 1938; New York: Grove Press, 1963), 236, 237. Third Epigraph: Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, ed. Edward B. Mitchell (New York: New York University Press, 1971), 94, 95.

2 Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, 88. Kermode declares, "Perfectly orthodox; obscenity is merely a matter of technique, of establishing the need of the artist to escape from l'immonde cité." Kermode is perfectly correct, although here, as when dismissing Miller's "very literary" disgust with "littérature" as a "tired posture at best" (86.), he attacks Miller's rhetoric of the 1930s as if it were a belated rehash of the overheated rhetoric of the 1930s. Kermode's allegiance to the "timeless tradition" of Joyce's achievement, and the fact that Miller, approaching age seventy, was still writing, combine to play tricks upon the critic's sense of history. He tends to forget that the author of Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring and Tropic of Capricorn was more Joyce's contemporary than his own, and that Ulysses was ushered into the world with much the same self-dramatizing, "revolutionary" rhetoric.

3 See Edward B. Mitchell, "Artist and Artists: The 'Aesthetics' of Henry Miller," and William A. Gordon, "The Art of Miller: The Mind and Art of Henry Miller," in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, 155-184: Mitchell and Gordon more persuasively argue the case to which Kermode had responded, but Kermode's anticipatory argument preemptively denies them the ground they would take.

4 Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, ed. Edward B. Mitchell, 94.

5 Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, ed. Edward B. Mitchell, 94.

6 Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, ed. Edward B. Mitchell, 86.

7 It is no "accident of nature" that Miller's "Burlesk" mimics the language of Stuart Gilbert's James Joyce's 'Ulysses' in the passages cited at the beginning of this chapter.

8 Frank Kermode, "Henry Miller and John Betjeman," Puzzles and Epiphanies, reprinted in Henry Miller: Three Decades of Criticism, ed. Edward B. Mitchell, 94.

9 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer (Paris: The Obelisk Press, 1934; New York: Grove Press, 1961; New York: Ballantine Books, 1973), 2.

10 A criticism based in semantics confronts the historical variety that is literary language with attempts to subsume temporal variations in practice under a universal, theoretical, spatial grid of class and sub-class, of rule and exception within the rule. As discussed in the second chapter, this is an effective way to construct and maintain Roland Barthes' genealogy of "text"--post-modern "text," modern "text" and the "text" in classic "works." See Roland Barthes, "From Work to Text," in Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977).

11 M. M. Bakhtin/P. M. Medvedev, The Formal Method in Literary Scholarship: A Critical Introduction to Sociological Poetics (1928); trans., Albert J. Wehrle (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 123, 124. Originally published as Formal'nyi metod v literaturvedenii (Kriticheskoe vvedenie v sotsiologicheskuiu poetiku) (Leningrad: "Priboi," 1928).

12 My list, already limited, is more parochial than Miller's would be, rather British-American in its omission of a host of French and German writers central to Miller's ambitious polemics, preeminently Proust and Freud. But my purpose here is not to "prove" exhaustively the "literariness" of Miller's novels, but rather to demonstrate that Miller's formal aesthetics, as a "losing" polemic within the discourse of the modern novel in English, have rendered his "literariness" largely invisible, whatever its extent.

13 As discussed in the third chapter, Miller, despite all his posing to the contrary, was one of the few American novelists of the 1930s to write directly from extensive critical reading. He took the relation between theory and practice as seriously as did his European contemporaries.

14 Jack Kahane, Memoirs of a Booklegger (London: Michael Joseph, 1939); quoted in Hugh Ford, Published in Paris: American and British Writers, Printers, and Publishers in Paris, 1920-1939 (New York: Macmillan, 1975; Yonkers, N.Y.: Pushcart Press, 1980), 363.

15 Henry Miller to Anaïs Nin (December 4, 1934), in Henry Miller: Letters to Anaïs Nin, ed. Gunther Stuhlmann (1965; New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons-Capricorn Books, 1976), 135-136. Miller transcribes two postcards received from Ezra Pound.