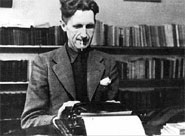

George Orwell on Henry Miller: Inside the Whale

George Orwell's most interesting essay -- in the technical sense -- of the puzzle that is Miller's status as an author of "literature" has been posted to the web, along with the rest of Orwell's published works, by the University of Newcastle, Austrailia.

Although "Inside the Whale" and Orwell's other works are still copyrighted in the United States, they've already passed into the public domain in Austrailia, under Austrailia's copyright limitation of 50 years after an author's death. So take advantage of the discrepancy and, if you've never read Orwell on Henry Miller and the other "high art" authors of his day, go down under for it [now] at "Inside the Whale" (1940).

(I won't comment, except in passing, on the Dead Hand effect of the "Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998," which extends copyright protection for 70 years past an author's death and, additionally, locks up everything published after 1923 until 2019, almost a full century. One should not be deceived that the purpose of this act is to advantage the children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and even great-great-grandchildren of creative talent, as if anyone ever deserved financial compensation for the accomplishments of a grandparent, let alone a great-great-grandparent. No, this act, which might better have been named the "Disney Mickey Mouse Profits Act of 1998," is designed to advantage the corporate exercisers of these "rights" against the domain of public interest. Why 1923? Must be just coincidental that 1923 was the year Walt Disney arrived in Hollywood with his sketchbook. Yes, I got you, babe with a vengeance.)

Continue reading "George Orwell on Henry Miller: Inside the Whale"

rri (April 12, 2005)

Kenneth Rexroth: The Reality of Henry Miller

Well worth reading, despite the blindingly tasteless turquoise background at www.bopsecrets.org, is Beat poet-translator-essayist-painter-anarchist Kenneth Rexroth's 1955 essay " The Reality of Henry Miller".

Rexroth (1905-1982), sometimes called "The Godfather of the Beats," originally wrote this piece as an introduction to Nights of Love and Laughter, a Signet anthology of publishable bits of Miller, whose Paris works were then still banned in the United States. "The Reality of Henry Miller" was reprinted a few years later in a New Directions collection of Rexroth's own essays, Bird in the Bush (1959).

Readers who've come to Miller through his 1960's "sexual liberation" guise or through the proto-New Age wisdom aura of the works of the last decade of his life will find much that is familiar in Rexroth, but also some strikingly different notes. It is, of course, those differences that are most interesting and illuminating.

Rexroth writing in 1955, obviously knowing nothing of what the future would bring, nothing of the later culture of the 1960s and 70s, helps us back to a Miller and a period of American "counter-culture" we almost cannot know otherwise, so steeped are we, without even thinking about it, in those subsequent blinding self-accountings and tsunami of commercializations of the Baby-Boomers' supposed "cultural revolution." Rexroth speaks to us from the distant other side of that - for better or for worse - cultural debacle, pointing to a Miller most of us growing up afterwards now only hazily discern.

Rexroth in 1955 still sees and appreciates Miller through the Beat preoccupation with authenticity, which was at once more political and less personal than that term now typically conveys, today so fallen into disuse.

Miller, the authentic, figures for Rexroth as some kind of cross between a "noble savage," a "modern primitive," and a better sort of "proletarian novelist" for neither being proletarian nor having a "social message." Miller is Rexroth's "religious writer" who is "not especially profound"; his "very unliterary writer" who "is not unsophisticated"; his Paris expatriate whose Paris is not so much Paris as it is still Brooklyn.

Miller, in short, is everywhere betwixt and between for Rexroth, this but not this, that but not that, because for Rexroth betwixt and between is fundamentally how one falls through "the Great Lie, the social hoax in which we live" to get to the Outside, to become authentic, to join the Others, also authentic for having fallen through America's cracks.

Thus Rexroth's most un-Sixties, un-PC, positive celebration of Miller and the politics of non-voting:

Fifty percent of the people in this country don't vote. They simply don't want to be implicated in organized society. With, in most cases, a kind of animal instinct, they know that they cannot really do anything about it, that the participation offered them is a hoax. And even if it weren't, they know that if they don't participate, they aren't implicated, at least not voluntarily. It is for these people, the submerged fifty percent, that Miller speaks. As the newspapers never tire of pointing out, this is a very American attitude. Miller says, "I am a patriot - of the Fourteenth Ward of Brooklyn, where I was raised." For him life has never lost that simplicity and immediacy. Politics is the deal in the saloon back room. Law is the cop on the beat, shaking down whores and helping himself to apples. Religion is Father Maguire and Rabbi Goldstein, and their actual congregations. Civilization is the Telegraph Company in Tropic of Capricorn. All this is a quite different story to the art critics and the literary critics and those strange people the newspapers call "pundits" and "solons."

Odd how tellingly this reads today: how "American," now that America, politically, socially, internationally, has lost its delusory post-1960's lustre; all its universal human promises and isms faded into pc-schoolboy and pc-schoolgirl gender-neutral, inverted-colorist catechisms. Odd how tellingly Rexroth from 1955 reads today, now that America has become once again, as in Rexroth's 1950s, a place, a symbol in which a great many of us with rather not be implicated, at least not voluntarily.

Perhaps, too, Miller answers today in ways he could never answer as an icon of "sexual liberation" or the wise hermit of Big Sur. Perhaps Miller, through his Paris writings, answers today, not from Rexroth's (or Miller's) 1950s, but from Miller's own 1930s, witness to the western world's seemingly unstoppable slide in fascism and war:

Life is just a mess, full of tall children, grown stupider, less alert and resilient, and nobody knows what makes it go - as a whole, or any part of it. But nobody ever tells.

Henry Miller tells.

rri (February 1, 2005)

Henry Miller at Literary Traveler

The interpretive biographical essay on Miller at Literary Traveler by freelance writer Jeffrey John Shea, "Henry Miller and The Dance of Life," is well written and worth reading, distinguishing itself on both scores from the typical recitations of clichés about Miller that abound elsewhere on the web.

As it happens, I don't particularly agree with this writer's interpretation of Miller's life and the "spirit of his art," but don't let that stand in the way of your reading, enjoying, learning, and even being inspired by it. Not just writing but reading literature has ever been an act of fiction, of fabrication, of imagining a lying wholeness, sense, and sequence to the lives of authors as fully as to the truly fictive existences of their characters. All, no doubt, the better to gain leverage in the all-consuming task of deceiving ourselves about ourselves.

The Literary Traveler offers a great deal more that might be of service on that score. The site is the inspiration of Linda and Francis McGovern, a couple who, whatever their fate, at least seem to have had their priorities straight at one point in time: to travel and to write. I envy them to the extent of their success!

And, yes, I like this well-executed site's business model. Poke around the edges and you'll see what I mean. Maybe even take a tour.

"Great literature, like great travel is essentially about experience, one you read, the other you live, both reveal what is true. That's what we are trying to do with Literary Traveler." - Linda McGovern

"We hope that when people read a book, and then visit Literary Traveler to learn about the author, and the places they lived and traveled - they become inspired to read and travel more, and maybe they even start writing themselves. They start exploring their literary imagination - they become part of what they have read and it is always with them." - Francis McGovern

rri (January 15, 2005)

The Henry Miller Library at Big Sur

By far the most visited Miller Site on the web, The Henry Miller Library is incommensurably better in reality.

Located in Big Sur, California, 35 miles south of Carmel-by-the-Sea on Highway One, the Library occupies the former home of long-time Miller friend Emil White, who established it as a fitting permanent memorial to Miller and especially to his years writing and painting in Big Sur (1944-1962).

If you've never driven California's famous winding, two-lane coast highway through the Big Sur region, definitely make plans to do so before you die. Use Miller as an excuse. Stop at The Henry Miller Library and buy a copy of Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. And while you're at it, go read it over an "Ambrosia Burger" at the cliff-hanging Nepenthe Restaurant just up and across the road. Whether you drive up the coast past Hearst Castle or down through Monterey Bay, you'll never regret it. Good weather and a convertible highly recommended.

I'll post pictures here when I manage to dig them out. Better yet, I may have to go back just to take some more.

rri (January 6, 2005)