7. Desire in the Waste Land

Desire in the Waste Land - Notes

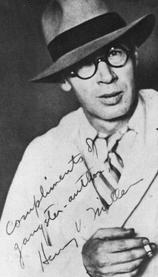

1 First Epigraph: Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn (Paris: The Obelisk Press-Seurat Editions, 1939; New York: Grove Press, 1961), 113-114. Second Epigraph: F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins, Paris (ca. December 10, 1924); in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, ed. John Kuehl and Jackson Bryer (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971), 89.

2 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1925), 69.

3 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 43, 44.

4 Miller's novel begins: "I am living in the Villa Borghese. There is not a crumb of dirt anywhere, nor a chair misplaced. We are all alone here and we are dead." It begins, that is, in parody of T. S. Eliot's polite despair: "He who is living is now dead/ We who are living are now dying/ With a little patience." (Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer [Paris: The Obelisk Press, 1934; New York: Grove Press, 1961; New York: Ballantine Books, 1973], 1.)

5 F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins, Hollywood (June 6, 1940), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 263. Fitzgerald adds, "He and Marx are the only modern philosophers that still manage to make sense of this horrible mess--I mean make sense by themselves and not in the hands of their distorters."

6 Jay Martin, Always Merry and Bright: The Life of Henry Miller (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Capra Press, 1978; New York: Penguin Books, 1980), 131.

7 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West (New York: Random House-The Modern Library, 1962), 218. "An abridged edition by Helmut Werner. English abridged edition prepared by Arthur Helps from the translation of Charles Francis Watkins." Originally published in two volumes as Der Untergang des Abendlandes, Gestalt und Wirklichkeit and Der Untergang des Abendlandes, Welthistorische Perspektiven (Munich: C. H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1918 and 1922). First American publication: The Decline of the West, Volume I: Form and Actuality and The Decline of the West, Volume II: Perspectives of World-History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926 and 1928).

8 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, 251-252.

9 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, 267.

10 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 1.

11 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 3.

12 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 36.

13 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 69.

14 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 59.

15 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 59-60.

16 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 44.

17 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 113.

18 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 91.

19 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, 267.

20 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 62.

21 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 56. The literally obscene--"off stage"--quality of work in Nick's narrative does not escape his attention, although he does little to rectify it:

Reading over what I have written so far, I see I have given the impression that the events of three nights several weeks apart were all that absorbed me. On the contrary, they were merely casual events in a crowded summer, and, until much later, they absorbed me infinitely less than my personal affairs.

Most of the time I worked.

After a paragraph describing commutes, lunches, and an office affair, Nick leaves the world of work for good. The only other mention of the bond business comes when Nick turns down Gatsby's offer of a deal on the side.

22 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 8.

23 Edward Dahlberg's Bottom Dogs (1930), reprinted in Bottom Dogs, From Flushing to Calvary, Those who Perish, and hitherto unpublished and uncollected works (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1976), is the most notable exception to the expatriate rule against representing work. The local color/ethnic/proletarian novel movement was largely domestic, conducted on the whole by those who, though they may have traveled to Paris, did not join the expatriate community. The novels of Dos Passos, like almost everything about Dos Passos, are ambivalent: his characters appear in work situations, but generally do not narratively "pursue" their work. Miller has Dos Passos and Hemingway in mind when he writes, "It is customary to blame everything on the war."

24 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 39. Miller connects the two worlds in the person of a veteran who comes to his office looking for work.

25 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 4.

26 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 58.

27 As the sequence suggests, in both books women, as objects of sexual desire, are caught halfway between objective and subjective "goods."

28 There are doubtless as many ways of selling a commodity as there are tropes; one might begin to construct a parallel listing, except for the suspicion that the average used car salesman is more resourceful than the most encyclopedic medieval rhetorician.

29 F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins, Paris (May 1, 1925), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 104.

30 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 92.

31 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 94.

32 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 97.

33 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 112.

34 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 111.

35 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 92.

36 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 192-193.

37 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 61-62.

38 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 94.

39 Metonymic desire keeps life drifting by the show window just as the "installment plan," as Miller describes it, keeps people buy to make each other happy. (Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 309-312.)

40 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 195, 196.

41 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 5, 182.

42 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 23. Generally overlooked in this process of canonization is the fact that Fitzgerald reaches further into the American poetic past than to T. S. Eliot of 1922 in order to authorize Gatsby's Waste Land. The description of the "valley of ashes" and last line of the first chapter--"When I looked once more of Gatsby he had vanished, and I was alone again in the unquiet darkness."--darkly echo William Cullen Bryant's "The Prairies":

THESE are the gardens of the Desert, these

The unshorn fields, boundless and beautiful,

For which the speech of England has no name--

[lines 1-3]

As o'er the verdant waste I guide my steed,

Among the high rank grasses that sweeps his sides,

The hollow beating of his footsteps seems

A sacrilegious sound. I think of those

Upon whose rest he tramples. Are they here--

The dead of other days?--and did the dust

Of these fair solitudes once stir with life

And burn with passion? [....]

[lines 35-42]

[....] All at once

A fresher wind sweeps by, and breaks my dream,

And I am in the wilderness alone.

[lines 122-124]

(Poems, "Red-Line Edition" [New York: Appleton & Co., 1872].)

43 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 45-46, 54, 176.

44 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 45-46.

45 F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins (October 27, 1924), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 80:

The book is only a little over fifty thousand words long but I believe, as you know, that Whitney Darrow has the wrong psychology about prices (and about what class constitutes the bookbuying public now that the lowbrows go to the movies) and I'm anxious to charge two dollars for it and have it a full size book.

46 Solomon Stoddard (1643-1729), after whom the Stoddard Lectures are named, was a graduate and briefly the librarian of Harvard College. Later the minister of a Northampton Congregation he introduced what became known as "Stoddardeanism" in response to the failure of the Half-Way Covenant to raise church interest and attendance, allowing that an individual's profession of faith was sufficient for church membership and admission to communion, rather than predicating admission upon the witnessing of some experience of grace. See William Rose Benét, The Reader's Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1965), s.v. "Stoddard, Solomon."

David Belasco (1859-1931), an American actor, producer, and dramatist advocated greater stage realism: he was widely known for his use of innovative lighting to produce "skies," and his insistence upon using real objects for stage properties. His The Girl of the Golden West (1905) served as the basis for the first grand opera written on an American theme, Puccini's La Fanciulla del West (1910). See William Rose Benét, The Reader's Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1965), s.v. "Belasco, David."

47 I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism (1925; New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich-A Harvest/HBJ Book, n.d.), 203-204.

48 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 24-25.

49 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 332: "I am an explorer who, wishing to circumnavigate the globe, deems it unnecessary even to carry a compass." I have quoted this passage previously.

50 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 200.

51 Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie, ed. Donald Pizer (New York: W. W. Norton-Norton Critical Edition, 1970), 17. The text, except for two typographical corrections, is that of the 1900 Doubleday, Page and Company first edition.

52 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 200, 201.

53 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 200-201. Frederick Schilling, of Library of America, points out that here Miller does not stray far from popular culture, for his "immutable self" is an over-writing of Superman, the most famous "real schizerino" to emerge from New York's Metropolis in the 1930s. In this regard Miller appears to have surpassed the most "Marxist" interpreters of the Superman myth, by identifying the "X-Ray" desire to "lift a skirt here and there looking for a letter box," and to leap tall buildings in a single bound as a "morganatic ailment," a direct consequence of American marketing techniques.

54 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 57.

55 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 95-96, 97, 97.

56 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 57-58.

57 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 98.

58 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 57; preceding the first passage quoted above: "I began to like New York, the racy, adventurous feel of it at night, and the satisfaction that the constant flicker of men and women and machines gives to the restless eye. I like to walk up Fifth Avenue and pick out romantic women[....]"

59 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 182.

60 F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins, Paris (January 24, 1925), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 93.

61 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 117.

62 F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins, Paris (ca. December 20, 1924), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 90.

63 Daisy's one apparent protest--"'All right,' I said, 'I'm glad it's a girl. And I hope she'll be a fool--that's the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.'"--is quickly resolved into disingenuity:

The instant her voice broke off, ceasing to compel my attention, my belief, I felt the basic insincerity of what she had said. It made me uneasy, as though the whole evening had been a trick of some sort to exact a contributory emotion from me. I waited, and sure enough, in a moment she looked at me with an absolute smirk on her lovely face, as if she had asserted her membership in a rather distinguished secret society to which she and Tom belonged.

(F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 17, 18.)

Mara is the only woman in Tropic of Capricorn who threatens "Miller." Her only recorded words are of outrage--"'suddenly for no reason at all, he bent down and lifted up my dress," and these are a fragment from "the little womb in her throat hooked up to the big womb in the pelvis." (Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 343, 343-344.)

64 A commercially conscious artist worried about censorship, Fitzgerald presents what Kate Millet calls a "more diplomatic or 'respectful' version" of the fear and loathing that finds unrestrained expression amid Miller's obscenities. (Kate Millet, Sexual Politics [New York: Doubleday and Company, 1970; New York: Avon Books, 1971], 389.) But whatever "diplomacy" Fitzgerald practiced in The Great Gatsby, it was lifted in his letters where, despite "excellent reviews," he anticipated slow sales because "the book contains no important women characters and women control the fiction market at present." (F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins (ca. April 24, 1925), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 101.)

65 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 197: "It was about this time, adopting the pseudonym Samson Lackawanna, that I began my depredations."

66 It is this version of commodity desire that Marx treats in the famous Shakespearean passage from the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, where he writes of money's metaphoric power as "the external, common medium and faculty for turning image into reality and reality into a mere image." On the exchange of women in traditional cultures, see Marshall Sahlins, Culture and Practical Reason (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976). Sahlins, however, persists in the American anthropological tradition of using "symbol" for every trope of value.

67 Henry James' The Golden Bowl might be considered a complex instance of such a market-based novel of consumer culture. Despite the surface narration in which women speak, act, and "motionlessly see" to achieve their own ends, the "reality" of the novel is more traditionally structured: commodities, art, knowledge, and women circulate in a complex network of good and bad faith exchanges between men who rarely exchange words--Adam Verver and the Prince. James' consumer melodrama lies in Maggie Verver's effort to finalize her father's "deals" by separating the couples to prevent further exchanges from taking place. She battles in the market, trying to "go home" with her family's purchases. Underneath James' "balloons of consciousness," Maggie is the agent of the lawful, male social order that is the denouement of traditional comedy.

68 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 123.

69 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 112.

70 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 133.

71 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 180-181.

72 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 171, 174.

73 Miller's tales of his own sexual prowlings go to elaborate lengths to prove that women have no exchange value. At Far Rockaway Miller discusses Rita with her brother "Maxie the window trimmer"--"the first time I spied him he was standing in the show window dressing a manikin" (Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 207.):

Every time we started for the beach I was in hopes that his sister would turn up unexpectedly. But no, he always managed to keep her out of reach. Well, one day as we were undressing in the bathhouse and he was showing me what a fine tight scrotum he had, I said to him right out of the blue--"Listen, Maxie, that's all right about your nuts, they're fine and dandy, and there's nothing to worry about but where in hell is Rita all the time, why don't you bring her along some time and let me take a good look at her quim . . . yes, quim, you know what I mean." [....] Maxie didn't like the idea at all deep down. (Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 204-205.)

Maxie doesn't like the idea of exchange and Miller does not propose it seriously--he does not need to do so. The powerful, imaginative "train" of metonymic desire quickly puts Rita's "private and extraordinary quim" on public display like any other:

Now this is what is rather strange. . . . A few minutes after I thought of Rita, her private and extraordinary quim, I was in the train, bound for New York and dozing off with a marvelous languid erection. And stranger still, when I got out of the train, whom should I bump into rounding a corner but Rita her self. And as though she had been informed telepathically of what was going on in my brain, Rita too was hot under the whiskers. (Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 207.)

In the ensuing action all vestige of exchange is exorcised. Miller steals Rita's change to make up for the carfare Maxie departed without giving him: "But somebody had to pay for making me walk around in the rain grubbing for a dime." One of an infinite number of "quims" on display, Rita is not even worth carfare, but the story of Miller's return from Far Rockaway is worth seven pages of Tropic of Capricorn.

74 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 175. Here, in an extension of the rhetoric of desire that refutes Hymie, women are made to "pay" for the concept of "cunts" as private property--a concept upon which any legitimate exchange must be predicated. In contrast to Tropic of Cancer, there is a notable absence of whores in Tropic of Capricorn. Miller's aestheticization of his fictive reality is more thorough in the later novel: paying is incompatible with a world of consumption in which one should receive or take. Miller values the story, not the woman:

At least, that's how Curley related it to me. He was an outrageous liar, to be sure, and there may not be a grain of truth in yarn, but there's no denying that he had a flair for such tricks.

75 Kate Millet finds that "Miller's sexual humor is the humor of the men's house, more specifically the men's room. Like the humor of any in-group, it depends on a whole series of shared assumptions, attitudes and responses, which constitute bonds in themselves." Discussing the male-to-male bond of storytelling predicated upon misogyny, Millet, unstayed by New Critical modes of analysis, is one of the few critics to assess Miller's narrative as narrative. But she mistakes Miller's misogyny for intended humor even as she describes the condition of its disappearance: "But unless sex is hard to get, comic, secretive, and "cunt" transparently stupid and contemptible, the joke disappears in the air." As a description of the culture of reading that finds Miller "funny" this is directly to the point, but it misses the economy of desire in Tropic of Capricorn, where Miller demonstrates that there is nothing humorous about male storytelling, without leaving, for that, the discourse of misogyny. Millet's focus upon comedy is a by-product of the psychologism of her analysis, which finds the fantasy of power embodied in misogyny to be the "adolescent" anxiety of the "American manchild"--if only it were, then we could all just "grow up," as Millet's concluding evocation of the "spontaneous mass movements" of the 1960's generation of "youth" seems to hope. There is, however, very little that is "adolescent" about an exercise of political power that has sustained the social reality and discourse of patriarchy throughout recorded history. (Kate Millet, Sexual Politics, 398-399, 407, 474.)

76 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 258.

77 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 189-190.

78 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 197:

I was no more. I was not even a personal hard on.

It was about this time, adopting the pseudonym Samson Lackawanna, that I began my depredations.

Under the "depredations" of "Samson Lackawanna," Miller--knowingly according similar treatment to women and things--includes commercial and consumer activity, as well as sexual activity. This declaration precedes by a few pages the trip down the river of time to Bloomingdale's.

79 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 185.

80 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 190.

81 Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, 223-224.

82 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 331.

83 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 6-7.

84 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 339.

85 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 339-340.

86 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 100.

87 This use of Spengler is truer to his deed than to his word: Spengler means to put the "Feminine" outside language, but he "makes" women to fit his philosophy as surely as Fitzgerald and Miller make women to fit their aesthetics.

88 Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West (Modern Library, Abridged Edition), 355.

89 F. Scott Fitzgerald to Maxwell Perkins (June 1, 1925), in Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, 110. The critique is of the "man of the soil," the "natural" male counterpart to the earth-woman he "furrows."

90 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 25.

91 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 9-10.

92 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 9.

93 Cleanth Brooks, Modern Poetry and the Tradition (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1939), 172.

94 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 47.

95 T. S. Eliot, "'Ulysses, Myth, and Order," The Dial (November 1923); reprinted in Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot, ed. Frank Kermode (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich and Farrar, Straus and Giroux--A Harvest/Noonday Book, 1975), 178.

96 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 178.

97 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 182.

98 Cleanth Brooks, Modern Poetry and the Tradition, 172.

99 Cleanth Brooks, Modern Poetry and the Tradition, 171.

100 Brooks' "rehabilitation" of Eliot the strategist is, of course, propaganda in its own right--reenacting the meta-fiction of poetry through a recovery of the purely self-reflective poetic mind from the history within which it is unfortunate enough to find itself immersed.

101 Cleanth Brooks, Modern Poetry and the Tradition, 171.

102 Henry Miller to Anaïs Nin (March 7, 1933), in Henry Miller: Letters to Anaïs Nin, ed. Gunther Stuhlmann (1965; New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons-Capricorn Books, 1976), 84, 85. Miller seems to have lent the grammatical construction of one line to the substance of another in his recollection of "Man and Woman" from The Decline of the West: "The man makes History, the woman is History." and "The male livingly experiences Destiny, and he comprehends Causality, the causal logic of the Become. The female, on the contrary, is herself Destiny and Time and the organic logic of the Becoming, and for that very reason the principle of Causality is forever alien to her." (Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, 355, 354.)

103 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 345. The Talmudic tradition postulates an evil "first wife" for Adam--one who refuses to be subordinate to his will and is banished to the night air of the wilderness--in order to reconcile, among other passages, Genesis 1:27, 5:2--"in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them." and "Male and female created he them; and blessed them, and called their name Adam, in the day when they were created." with the sequential "rib" creation story of Genesis 2:7, 2:21-23. Isaiah 13:19-21 prophesies that fall of "Babylon, the glory of kingdoms, the beauty of the Chaldees excellency, shall be as when God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah. It shall never be inhabited[....] But wild beasts of the desert shall lie there; and their houses shall be full of doleful creatures; and owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there." (King James Version). See Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 35-44, for an account of the patriarchal function of the myth of Lilith and a suggestive parallel between Lilith and Eve and the Queen and Snow White of Grimm's Fairy Tales. They argue that the evil, plotting Queen and the imagistic Snow White are, mother and daughter, the same "Woman" set against each other by the strangely absent King (in the mirror). Mara and Daisy suggest a bifurcation similar to Lilith and Eve, the Queen and Snow White: they are Night and Day spirits who prove equally deceptive in the eyes of their male creators.

104 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 234.

105 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 98.

106 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 101.

107 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 240.

108 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 115.

109 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 341.

110 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 226, 227-228.

111 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 332.

112 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 223.

113 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 343-345.

114 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 100.

115 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 229.

116 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 230.

117 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 345-346.

118 Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn, 345-346.